Attachment Theory is a theory of psychological development formulated by psychiatrist and

psychoanalyst John Bowlby that maintains that humans are born with a need to form close emotional bonds with their care-givers. Bowlby proposed that humans are inherently relationship-seeking and that we especially need to seek contact with familiar, comforting others in times of need. We are hard-wired to seek and maintain proximity to supportive others when we are vulnerable. When our special other(s) are responsive to our needs, we can regulate our emotions, we learn important lessons about healthy relationships, and we can be braver going out into the world knowing our person is there to turn to if we need them. Paradoxically, being connected to others makes us more free to be autonomous. Attachment is a primary need that we never out-grow. Our need for loving and safe attachment figures is present “from the cradle to the grave”, as Bowlby so aptly put it. Our earliest care-giving relationships shape our expectations of close relationships but these expectations can change throughout our life as we gain experiences in close relationships. As adults, the close bonds we form with others (especially romantic bonds) are part of the same attachment process as when we were infants (Shaver & Mikulincer, 2016).

Key points of Attachment Theory

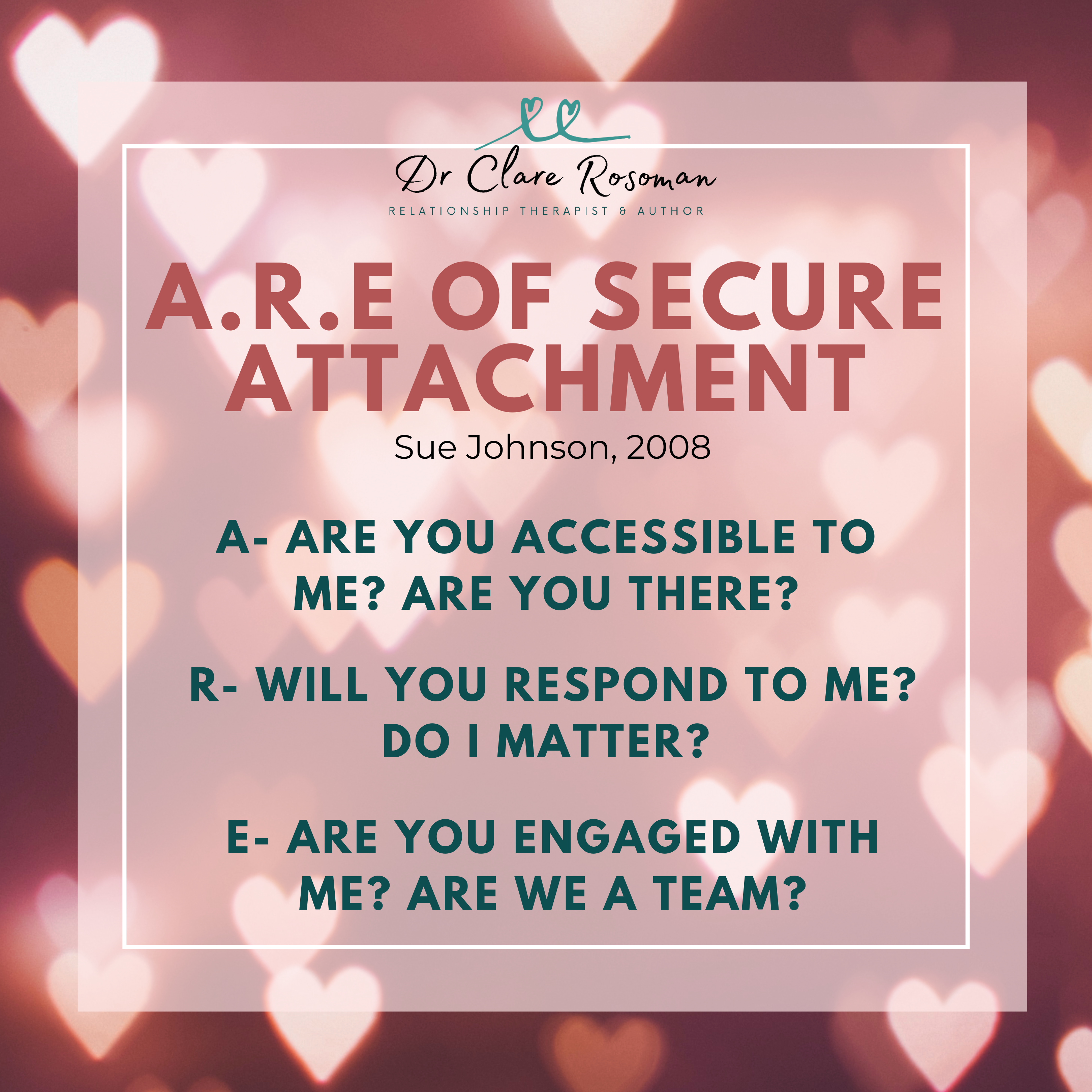

An attachment bond is a deep and enduring bond between two people where they are Accessible, Responsive and Engaged with each other. Sue calls this the “ARE” of secure attachment (Johnson, 2008).

Our earliest attachment bonds in childhood teach us about what it means to be close to another and about our worthiness of love, comfort and support.

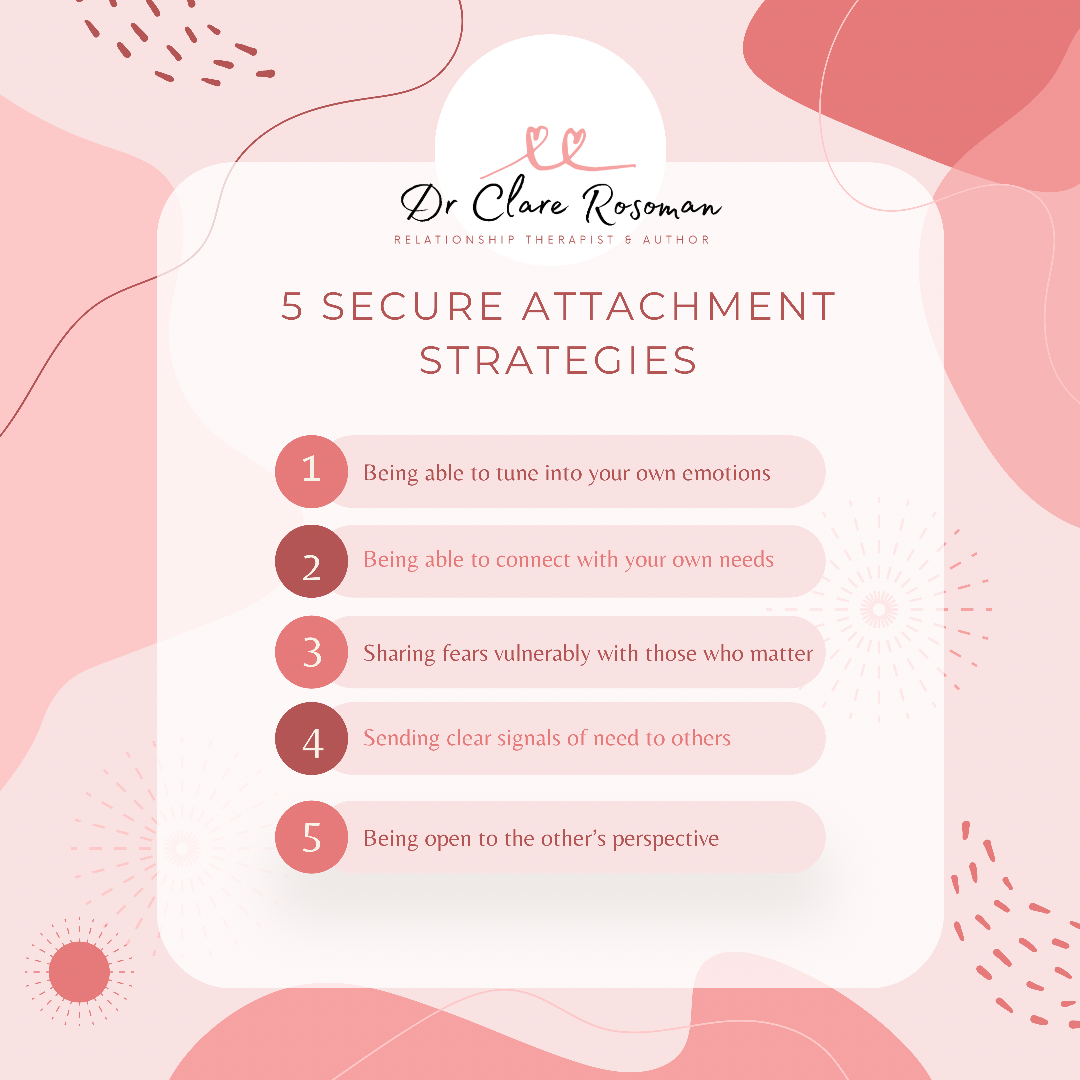

If our earliest care-givers are responsive to our bids for contact and safe to come close to, we learn that turning to others is an effective way of regulating our emotions and that we are worthy of comfort (Bowlby, 1988).

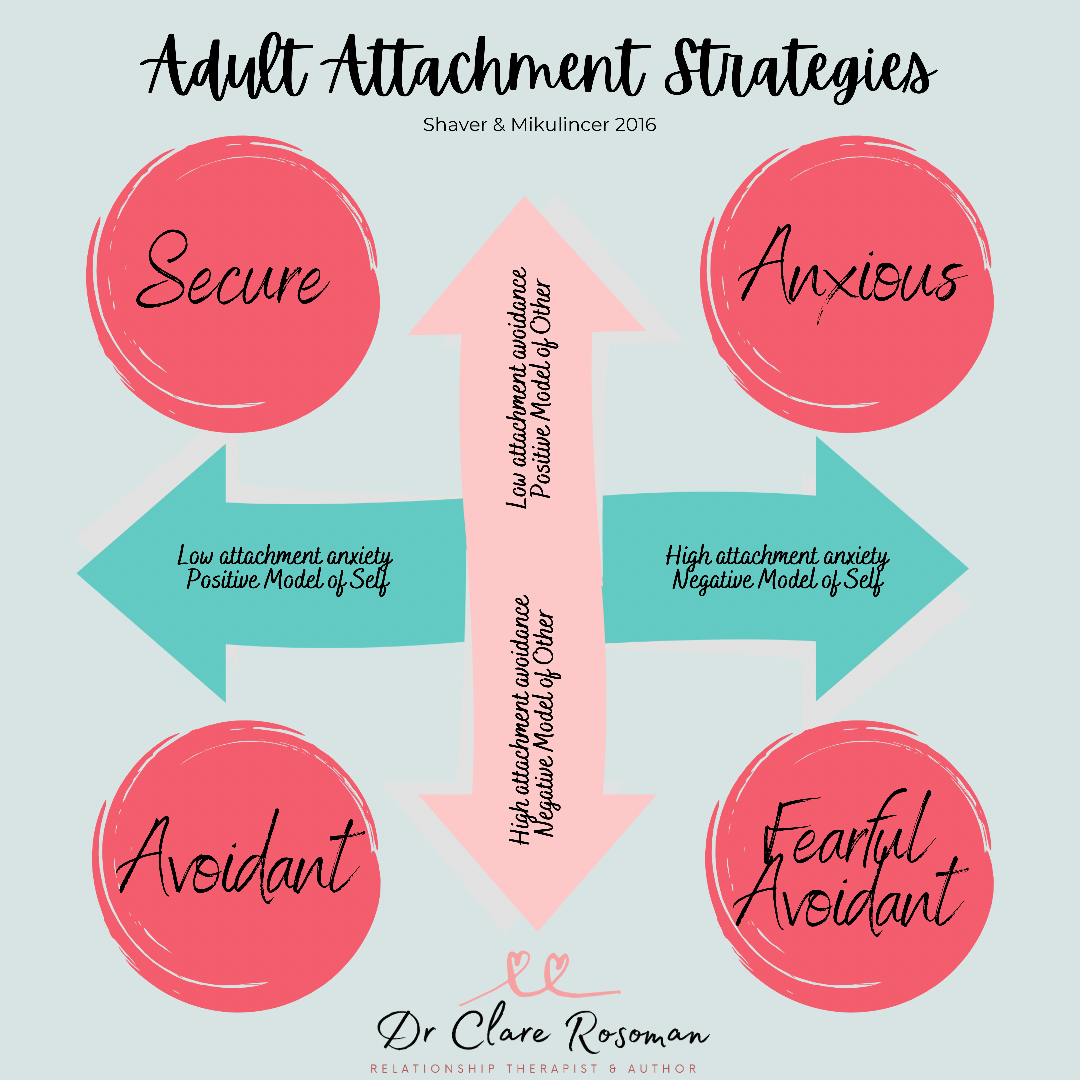

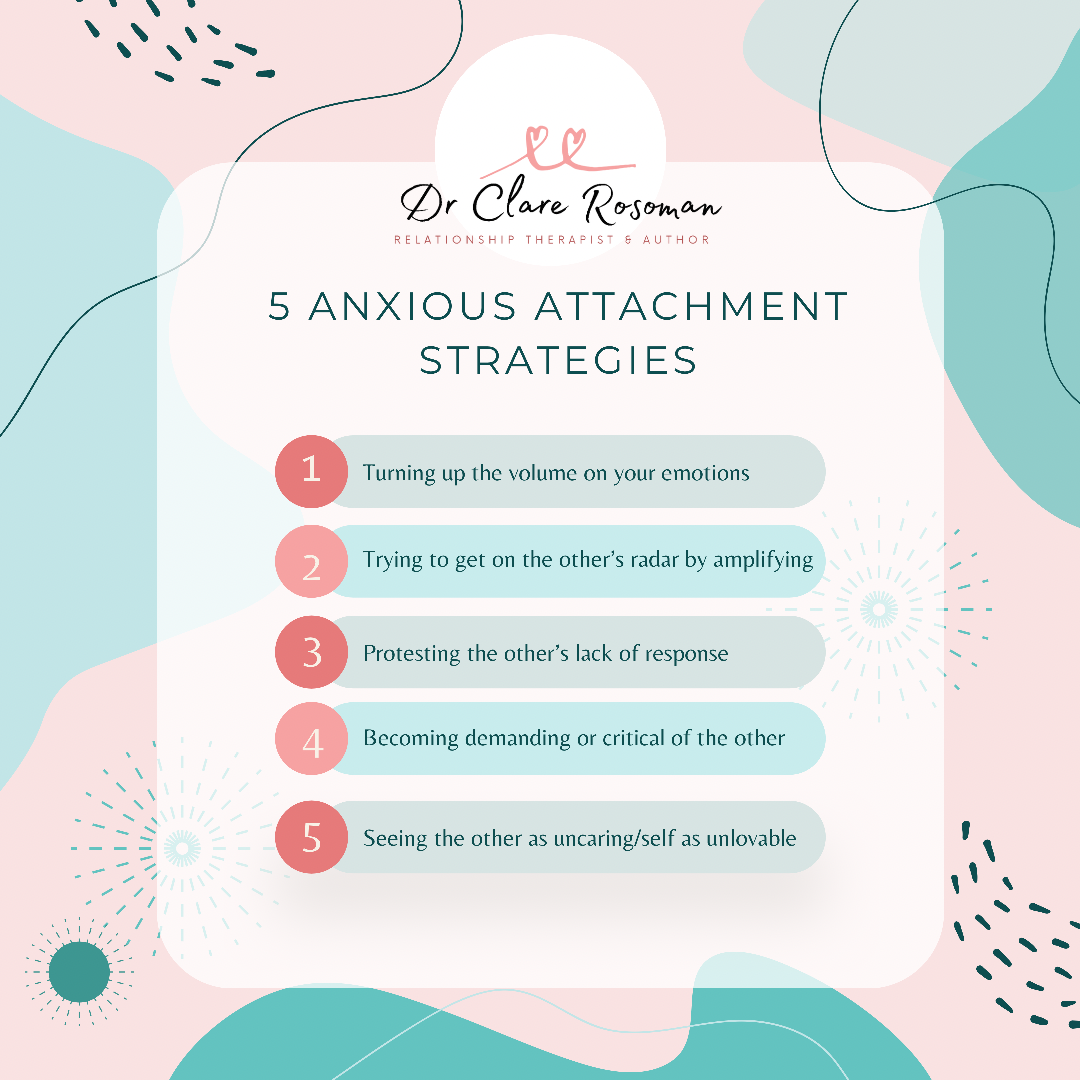

If our earliest caregivers are not responsive to our needs, we learn to turn up the heat of our emotional signals to ensure that they respond to us or to turn down our emotional signals and to cope alone.

Both of these “attachment strategies” (also called attachment styles) help us to cope when turning to another is not available to us. These are called “secondary attachment strategies” because they use more energy than the “primary” attachment strategy of seeking comfort from a safe other.

As humans, isolation is inherently traumatising. We are wired to form relationships – we are a bonding species.

We are also wired to co-regulate – to turn to others to share the emotional load, this uses less energy and is the most efficient way to cope (Coan & Sbarra, 2015).

Turning to safe others is not pathological or co-dependent. It is a biological imperative that Bowlby called “functional interdependence.”

When we know at least one special irreplaceable person in our life has our back and is there for us to turn to, far from making us dependent, it actually makes us braver. We can challenge ourselves to do difficult things when we know our person is there to turn to if things get hairy.

Why we need

Secure Attachment Figures

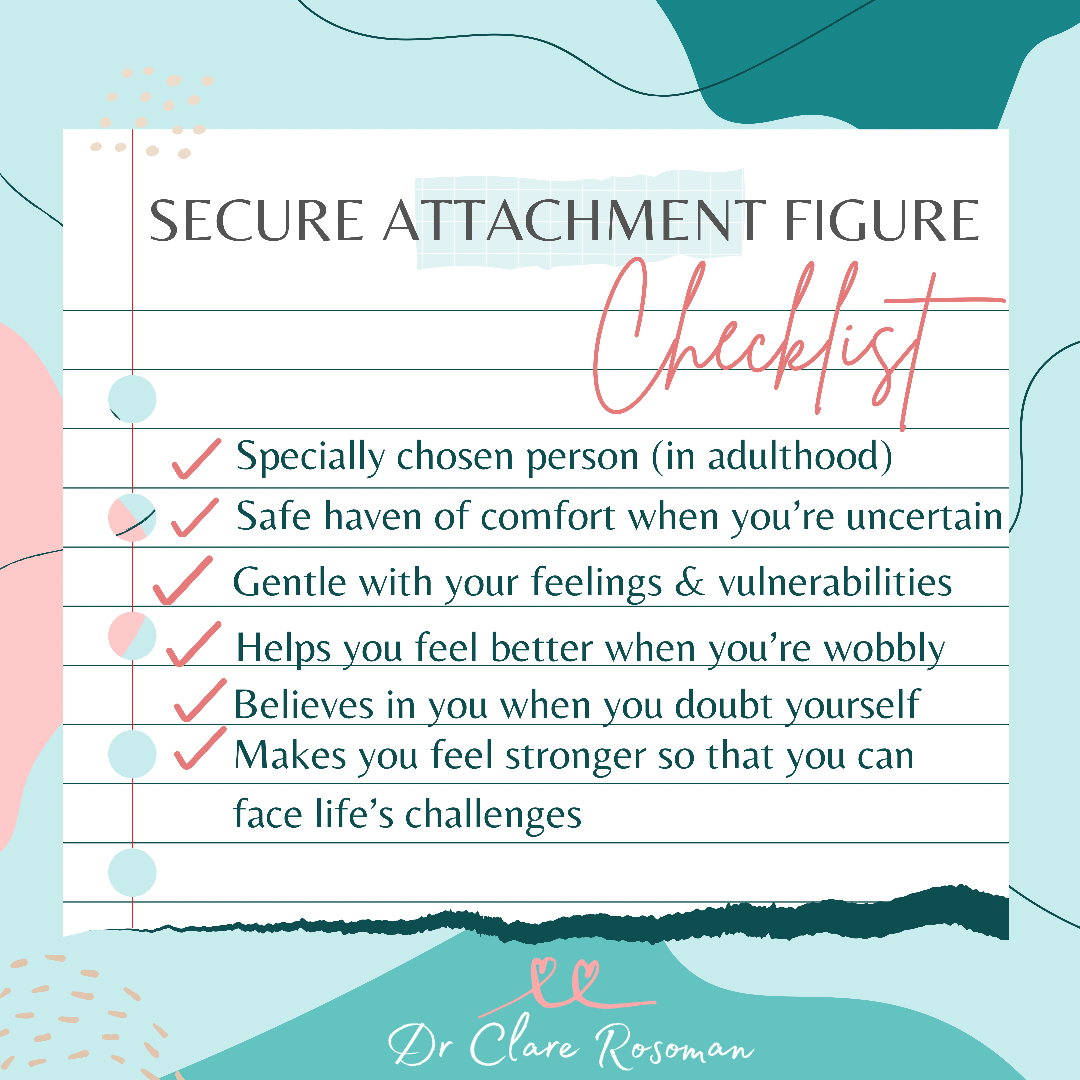

Safe haven

Secure attachment bonds in childhood and adulthood provide a “safe haven” of comfort to turn to when we feel upset, vulnerable, hurt, sick, or afraid. They are a place of solace where our nervous system can best regulate in another’s steady and safe presence. When we are responded to with comfort and support, we can regulate our emotions, can be with our experience without being overwhelmed by it, and can move through it more readily.

Secure base

Secure attachment bonds in childhood and adulthood not only provide comfort, they also play a vital role in building our confidence and autonomy. When we know that someone has our back, it actually makes us braver; better able to take on new challenges and to explore the world more confidently. Being able to call our attachment figure to mind is part of how we stay strong in difficult situations and regulate our emotions.

Buddhist view on attachments

When talking about the concept of attachment bonds with important people in our lives, this is different from the Buddhist principle of non-attachment. This principle teaches to let go of rigid views of self and others by practicing non-attachment (Baljinder & Shaver, 2013). While the use of the word “attachment” might take on many meanings, it is important to note that Buddhist advice is not to detach from people in your life or from experiences.

We are not affiliated with Attachment Parenting

The attachment parenting philosophy developed by William and Mary Sears aims to foster secure attachment through eight practices (including) breastfeeding, co-sleeping, constant contact (like baby-wearing) and emotional responsiveness. While well-intentioned, this approach has led to concerns over the advice being taken to the extreme. To date, there is no evidence that these practices are predictive of secure attachment. We do know that even in a secure attachment, parents are attuned to their baby only about 30% of the time (Tronick & Gianino, 1986). It turns out that “good enough” parenting (being there when it really counts, but not being “perfectly” responsive all the time) really is effective in fostering secure attachment in children – what a relief! (Woodhouse et al, 2020)

Videos About Attachment

Still-Face Experiment

This short video by Ed Tronick from the Child Development unit at Harvard shows us the power of care-giver responsiveness.

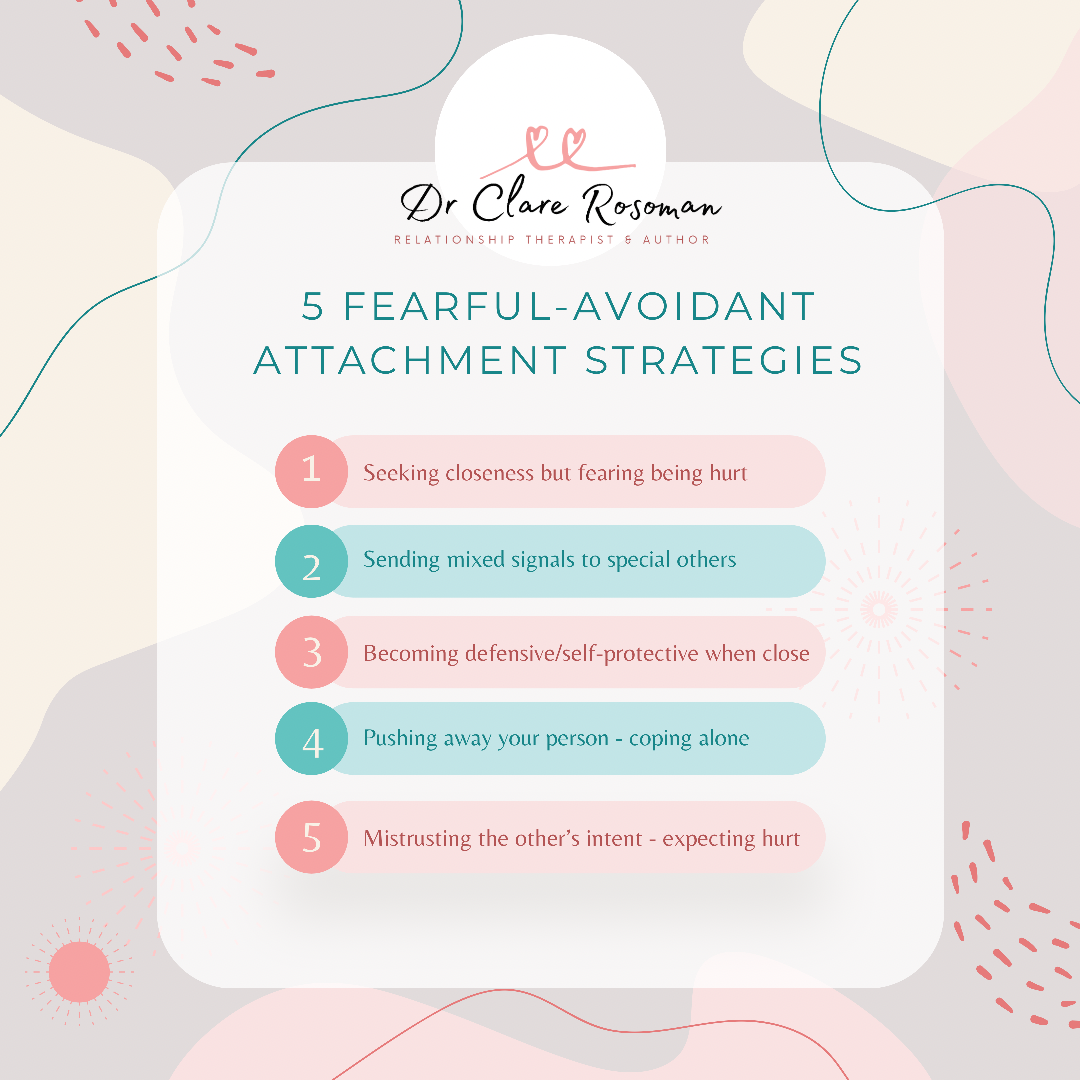

Watch videoAttachment Strategies

An overview of Attachment Theory and including the four key attachment strategies and how these strategies (styles) develop.

Watch videoDownload an information sheet on attachment theory

what is attachment?References and further Reading

Baljinder, K. S. and Shaver, P. R. (2013). Comparing attachment theory and Buddhist psychology. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 23, 282-293.

Bowlby, J. (1988). A Secure Base. New York: Basic Books.

Coan, J.A. & Sbarra, D.A. (2015) Social baseline theory: The social regulation of risk and effort. Current Opinion in Psychology, 1, 87-89.

Johnson, S. M. (2019). Attachment Theory in Practice: Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT) with Individuals, Couples and Families. New York: The Guildford Press.

Johnson, S. M. (2008). Hold Me Tight: Seven Conversations for a Lifetime of Love. New York: Little, Brown Book Group.

Shaver, P. R. and Mikulincer, M. (2016). Attachment in Adulthood: Structure, Dynamics and Change 2nd Ed. New York: The Guildford Press.

Tronick, E. Z. and Gianino, A. (1986). Interactive mismatch and repair: Challenges to the coping infant. Zero to Three, 6(3), 1-6.

Woodhouse, S. S., Scott, J. R., Hepworth, A. D. and Cassidy, J. (2020). Secure base provision: A new approach to examining links between maternal care-giving and infant attachment. Child Development, 91(1), e249-e265.